mirjam hemström farsi

WRITING

Relationen mellan hand, verktyg och maskin fängslar mig. Den är laddad. Symboliserar alltifrån hantverk och kultur till arbetsförhållanden och klimatkris, och ger mig emellanåt en känsla av att måsta ta ställning. Genom arkeologiska fynd och avställda, gamla maskiner, berättar den vår historia. Den säger något om tid. Och så berör den det där jag längtar efter: den både sinnliga och andliga upplevelsen.

Vad är en människa? En människa kännetecknas av bland annat stor hjärna, språk och teknologi. Det sistnämnda kan översättas “systematisk framställning” och ordet härstammar ur grekiskans teʹchnē som betyder konst eller hantverk. Teknik har, enligt lexikonen, i synnerhet att göra med läran om industriella tillverkningsmetoder. Vi skapar saker. Med våra huvuden, med våra kroppar och med verktyg.

Förmågan att använda redskap och tillägna oss ny kunskap har varit avgörande för vår arts utveckling. De äldsta fynden av mänsklig bearbetning består av enkla, spetsformade stenredskap vilka användes för att hugga och skrapa. När människan blev samlare och började bära med sig ting, fördjupades hennes förhållande till redskap ytterligare. Redskapens evolution har varit viktig för hantverkets tekniska utveckling.

Ett verktyg är ett redskap för bearbetning av material, ett hjälpmedel avsett att användas för hantverksmässig framställning. Det kan syfta på en kroppsdel som medel för utförande av en specifik funktion, men oftast åsyftas ett hjälpdon att hålla i handen. En av de få djur som medvetet använder verktyg är sjöuttern. För att öppna ett musselskal balanserar den en sten på magen medan den slår musselskalet mot stenen. Jag blir rörd av detta. Den flytande uttern som bankar musselskal mot sten tillhör mina mest frekvent använda GIF:ar då jag vill säga (ja vad är det jag vill säga?,) något till mina vänner.

Efter att muskelkraft och dragdjur länge varit den enda energin som fanns att tillgå, var nyttjandet av enkla redskap för att förstärka effekten av sitt stretande ett enastående genombrott. Hävstången, hjulet, kugghjulet och så småningom även vind, vatten, ånga, gas, olja och el har alla bidragit till människans avancemang.

Med fabrikssystemet, tekniken och kapitalismens framväxt förändrades villkoren för hantverkets roll och industrialiseringen har på ett markant sätt påverkat vår relation till objekten omkring oss. Som både industri- och handvävare upplever jag emellanåt en förvirring i de väsensskilda sätten att betrakta mitt material. Eller, åtminstone sättet på vilket jag identifierar mig med textila objekt. Det råder ingen tvekan om att såväl industri- som handvävning är hantverk. Men något skaver. I status på mitt material, i prissättning av arbetet.

När vi i dag talar om textil teknologi, syftas det ofta på teknik snarare än verktyg. En som utmanar dessa gränser är Hella Jongerius - en av världens mest hyllade designers. Med en bakgrund inom industridesign, är hon känd för sitt delikata sätt att blanda industri och hantverk, high- och low tech, traditionellt och samtida. Sedan 1993 driver hon studion Jongeriuslab i Berlin, som arbetar med både forskning kring betydelsen av färg och material och skapar produkter för gigantiska företag såsom KLM, Kvadrat och IKEA.

Jongerius har de senaste åren ägnat sig åt laboratorieliknande vävprojekt, där hon skolats i vävlära och som nybörjare tagit sig an tekniker och verktyg utifrån sitt designperspektiv. Det manuella, mekaniska och industriella kopplas samman i specialbyggda redskap, med syftet att ifrågasätta samtidens relation till textil. Genom att arbeta mot kulturinstitut och museiplattformar istället för att vara del av det stora maskineriet industrin, tillåts hon med lekfullhet pusha gränser och höja sin politiska röst.

I juni 2019 flyttade Jongeriuslab in på Galeries Lafayette i Paris. Under tre månaders tid tog utställningen Interlace, textile research form i lyxvaruhusets trapphus och omkringliggande rum, där kunderna fick en direkt inblick i den textila tillverkningsprocessen. I en värld av fast fashion där textil blivit en slit- och slängvara, syftade denna exponerade live-research till att belysa det problematiska i dagens konsumtion och textilproduktion, öka uppskattningen och få konsumenterna att ompröva värdet av materialet. På ett sätt förvandlades hela Galeries Lafayette till en maskin. Och där blir det intressant. När industrin närmar sig hantverket.

I år har Jongerius tagit sin väv-research vidare. På muséet Gropius Bau i Berlin tar Woven Cosmos form framför besökarnas ögon och designern bjuder in till upptäckter med öppna slut snarare än fixerade resultat.

Varför vävning, kanske någon icke-frälst frågar sig? När en materialflexibel industridesigner som arbetat i branschen i trettio år tar tempen på världen och kommer fram till att vävning är relevant i vår tid, ja då blir man nyfiken.

- Vävning erbjuder behövda perspektiv på samtida frågor om ansvar och hållbarhet, det är ett mångfacetterat ämne med såväl ekonomiska, sociala som kulturella aspekter. Innan den industriella revolutionen arbetade vi tillsammans. De senaste decennierna har vi blivit mindre medvetna om hur textil tillverkas och med det förlorar vi hantverkskunskap. Vävning finns i vårt kulturarv men är också framtiden: de nya, högteknologiska 3D-strukturerna är några av de starkaste, lättaste, minst energikrävande material som erbjuds byggindustrin.

Woven Cosmos verkar handla om att designa relationen mellan människa och objekt. Det rör sig om helande hantverk och föremål som inspirerar och kopplar samman. Jongerius menar att vår relation till objekten och till planeten har förgiftats, att fast fashion bidragit till en materialets fattigdom och att vi just nu ger iväg textilkulturen till industrin.

- Vi förlorar vår kultur. Behåll rikedomen! Behåll konstruktionsskickligheten!

Människor lever i dag delvis i en digital värld, i ett platt universum där fysisk taktilitet är frånvarande. Allt är för ögot och örat, inget för känseln och lukten, menar Jongerius. Detta är anledningen till att hon velat studera taktilitet, sensationerna som kommer genom handen. Kan ögat vara mer av ett kännande öga än ett seende?

Vad är taktilitet? Kan man känna fulhet eller skönhet? Jongerius uttrycker i en intervju om utställningen i Paris att våra ögon blivit kommersiella. Interlace, textile research var inte en utställning man kunde känna på med händerna. Däremot kunde man känna på skapandeprocessens snåriga stigar av försök och felsteg och ta tillbaka något av den individuella förståelsen som industrin och globaliseringen kidnappat.

Vid en intervju med Jongerius i samband med utställningen Woven Cosmos, får jag chans att fråga om handens roll. Jongerius svarar snabbt och med bestämd röst:

- Den är jätteviktig. I händerna finns lösningen. Vi behöver smarta händer för att hitta lösningar som hjärnan inte kan finna. Kunskap sitter i görande, rörande, taktilitet. Sedan kan man analysera, gå in i huvudet, digitalisera, producera industriellt. Men kunskapen sitter i händerna.

Ett verktyg är en förlängning av kroppen eller handen själv. Jag tycker om att tänka på maskiner som verktyg som, då jag känner dem tillräckligt väl för att kunna börja manipulera, kan anpassas efter mina syften. Vi tillverkar mer och mer avancerade verktyg och maskiner. Den globala handeln döljer processen för oss och gör det stundom svårt att relatera till processen bakom, och jag tror att om vi kunde överbrygga gapet mellan hand och maskin bättre, så skulle människors upplevelse av det vi skapar bli starkare. Genom vördnad inför verktyget kopplar vi till världen, den närliggande, strax utanför oss själva.

Att röra vid och att göra något repetitivt är helande. Liksom att arbeta tillsammans. “Varpgemenskap” sade någon i min vävgrupp en gång, då vi hjälptes åt att dra på en varp. Att göra i grupp är ett sätt att förstå ting på andra sätt än genom det estetiska. Energinivåerna fylls på, objekt syresätts genom våra händer. Hur ser tid ut? Möjligen som spår av människa. Att skönja händelseförlopp är att få syn på åtminstone en bit av vad det är att vara människa.

I vävheaven går hantverk och industriellt hand i hand och den rumsliga väven formges i ett hus tidigaste stadium. Varför? För att materialet är komplext och kommer bäst till sin rätt om det fångar upp det specifika rummets kvalitéer. Alltsedan industriella revolutionen har vi i det västerländska samhället byggt oss bort ifrån upplevelsen av objekten omkring oss, synen på ting har spätt på en oförmåga till finkänsel och vårt samhälle verkar ropa efter en sinnenas formgivning. Någonting saknas och jag tror inte att det handlar om ett val mellan hantverk och industri utan om kvalitet: vi behöver känslighet för och kunskap om perceptionen av materialet.

Den forna Bauhausskolan i Dessau, Tyskland, präglades av en optimism kring balansen mellan hantverk och maskin, och dess experimentlusta och nyfikna inställning till industrin är intressant än idag. “Enhet mellan konst och teknologi” - mums. I skolans textilverkstad undersöktes färg och form genom varp och väft. Arkitekturens vokabulär hade under många år närt det textila språket, men det saknades alltjämt termer och textilen började under det tidiga trettiotalet att låna begrepp från fotografiet som var på framväxt.

T’ai Smiths bok Bauhaus weaving theory: from feminine craft to mode of design skildrar hur Bauhausväverskorna kämpade för textilens plats inom designen på 1900-talet och vidgade begrepp såsom hantverk och konst. Jag kommer i denna artikel utgå från Smiths analyser av haptik och textil, då det var just denna bok som fick mig att så ihärdigt ligga på Göteborgs Bibliotek för att hitta fram originaltexten Stoffe Im Raum - Otti Bergers artikel om taktil-visuell väv på för mig obegriplig tyska.

Textil hade länge porträtterats som en del av en interiör, men 1931 hände det sig att Bauhaus julinummer publicerade en närbild av ett tyg på framsidan. Fotografiet blev linsen genom vilken textilens taktilitet blev synlig. Bakgrund: Det pågick en intensiv debatt kring hur fotografiet skulle användas i samhället och i kulturen. Redan 1709 uttrycktes inom optiken idén att eftersom ögonen endast kan se tvådimensionella mönster av ljus och färg för att uppfatta former och avstånd, kopplar hjärnan ihop dessa med minnen av känsel för att uppleva tredimensionalitet.

Konsthistorikern Reigl skrev om taktila och optiska metoder hjärnan använder för att tolka sin omgivning på och införde termerna optisch och haptisch i det konstnärliga språket - det verkade faktiskt som om världen utvecklades från närsynt haptisk till distanserat optisk. Med fotografiet började vi uppleva platser och rum genom bilder i tidningar och tack vare fotografiets utveckling fick Bauhausväven ett uppsving. I julinumrets omslagsbild syntes variationer i trådens tjocklek och mötet mellan varp och väft gav upphov till skuggor. Även tygveck och materialmöten skapade taktila sensationer. Genom närbilden förstärktes taktiliteten samtidigt som en spänning uppkom genom inzoomningens lovande, oändliga dimensioner.

Vävaren Otti Berger studerade på Bauhaus 1927–1930 och det var i kursen för László Moholy-Nagy, kämpe för taktilitetens nödvändighet för sinnesförnimmelserna, som olika känselegenskaper såsom tryck, stick, gnuggning, smärta, temperatur och vibration undersöktes envar och i kombination. Berger kartlade olika material och deras optiska och taktila kvaliteter, och genom kombinationer av färg, form och material fick hon syn på hur olika egenskaper tycktes överlappa varandra eller smälta samman i en och samma yta.

Ingen annan Bauhausvävare kom att plädera lika starkt för taktilitet som textilens primära kvalitet. I tidningen ReD från 1930 finns artikeln Stoffe Im Raum (Tyg I Rum), där Berger behandlar ett länge förvanskat ämne: olika materials taktilitet i relation till kinestetik (kroppens rörelse i relation till ett objekt). Artikeln blev en del av debatten kring det sinnligas status hos objekt. Berger tog avstamp i tidens diskussion kring fotografiet som ett optiskt medium och utvecklade detta resonemang genom att visa hur textilen inte enbart var ett optiskt objekt, utan även, och kanske till och med primärt, ett taktilt sådant. Hon använde ordet grepp (griff) och genom att påvisa skillnaden mellan greppa som i att ta tag i med händerna och greppa som i att förstå, målades sambandet mellan visuella och taktila kvalitéer fram. Under åren ökade hennes önskan om förståelse för textilers haptiska egenskaper i relation till rumslig formgivning, eftersom hon såg att textiler i rum upplevs både genom beröring, syn och rörelse. Berger skrev om ett “taktilt minne”, om textilers förmåga att inte enbart kännas taktila vid beröring utan även upplevas taktila i det omedvetna. Upptäckten av växelverkan mellan optiska och taktila element och arbetet för att applicera teorin i rummet, gör henne till en avantgarde till dagens textila arkitektur.

Haptisk perception, eller haptisk uppfattning, betyder bokstavligen “förmågan att förstå något”. 1892 myntade psykologen Max Dessoire termen haptik som namn för forskningsområdet känselförnimmelser och det har vidare beskrivits som ”individens känslighet för världen intill hans kropp med hjälp av hans kropp”. I dagens digitala värld används haptisk teknik i stor utsträckning både inom virtual reality och i tvådimensionella bilder som upplevs tredimensionella eller taktila. I Human Haptic Perception av Martin Grunwald föreslår psykofysiska studier att makrospatiala egenskaper såsom ett objekts form är starkt kopplat till synen, medan känseln är mer mottaglig för mikrospatiala egenskaper, det vill säga textur.

Berger menade att en måste kunna greppa textilens struktur med händerna. Matad som jag är med dagens diskussion kring vikten av hantverk, undrar jag om hon också tänkte på struktur som kunskapen om textilens produktionsprocess. Moholy-Nagy menade att en färdig produkt kan säga något om processen: naturens påverkan, behandling av materialet eller mekaniska processer påverkar upplevelsen av produkten, och han illustrerade teorin med bilder av en rynkig människa och en skrumpen frukt. Synbart åldrande låter oss skönja händelseförlopp. Och vi kan föreställa oss en historik, en process som lämnar spår.

Moholy-Nagy använde begreppet “facture”, som kan översättas till fabrik men även struktur (vilka båda har med tillverkning att göra). Om den haptiska perceptionen sitter i den tidigare erfarenheten - betyder det i sådana fall att ett material av i dag kan kännas mindre för att det produceras dolt för oss, i en annan del av världen? Jag tittar på bilder av mina maskinvävda monofilamentvävar och funderar på om de har höga eller låga haptiska nivåer. Jag vävde dem i syfte att försöka förstå hur haptiska textiler skulle kunna se ut idag. Jag tittar och tittar och försöker se hur vävarna känns. Men jag känner det inte.

Är det kylan i det artificiella materialet? Eller är det det maskinvävda? Det känns konstigt att jag inte vet om vävarna är superhaptiska eller haptikfattiga. Kan det vara så att många av dagens material är formgivna med optiska syften snarare än taktila, liksom Riegl menade att vi gått från närsynt haptiskt till distanserat optiskt, och att vi till viss del förlorat förmågan att uppleva material? Skulle vi uppleva taktiliteten starkare om vi kände till tillblivelseprocessen? Det finns ett stycke i Thinking Through Craft av Glenn Adamson som jag ibland återkommer till:

"Once Yagi was asked to name the essence of ceramics. Was it the wheel, the traditional tool of the potter? No, it’s not the wheel, Yagi replied. It’s the feeling you get when you take soft clay and squish it between your fingers. That’s the essence of clay for me."

Keramikens själva kärna verkar enligt den japanske keramikern Yagi bo i produktionen, eller knappt produktionen – snarare okynnesleken med materialet. Det verkar finnas ett samband mellan haptik och produktion.

Det sägs att när Alvar Aalto formgav MIT Dormitory Baker House så tog sig Aalto till tegelstensfabriken själv och valde ut de fulaste, mest ojämna tegelstenarna han kunde hitta. I fasaden skapar dessa andrasorteringens tegel en fängslande yta som bär spår av tillverkningsprocessen. Väggen biter sig fast i minnet och förundran över ojämnheternas skuggspel, panelsamtalet mellan sol och material, får sinnet att fantisera om hur själva byggandet och kompositionen gick till. Fabrikationen av textil är laddad för den spänner över världsdelar, arbetsförhållanden, fast-fashion, ohållbar konsumtion, ekonomi, hantverk och kultur, och tydligt är att industrialiseringen påverkat vårt sätt att uppleva objekten omkring oss.

I artikeln Stoffe und neues Bauen (Tyg och Nybygge) från 1933 skriver Berger, inspirerad av arbetet för ett inredningsdesignföretag, att för att textilen ska kunna svara på de rumsliga kraven och hamna i ömsesidigt förhållande med en ny byggnad, måste textilens roll i arkitekturen redas ut. Det verkar som att Berger önskar haptisk textil i jämställd dialog med arkitekturen, och jag tror att det finns något här, i perspektivet på tid. Platsen vördas med nogsamt utformad väv. Platsspecifikt konsthantverk.

Väv är ett högst haptiskt material som kan upplevas såväl objektivt som subjektivt. Det verkar finnas flera sätt att tillfullo uppleva rumslighet. Närheten till materialet, såväl genom kamerans inzoomning som genom tillblivelseprocessen och för att inte tala om den fysiska, är alla starka recept. Väven är nära, mångfacetterad. Och den har allt att göra med rum.

Franz Kafka skrev i sina memoarer att “alla bär på ett rum inom sig” och nog är det ett textilt rum vävaren ser framför sig. Att väva rum är inget nytt under stjärnhimlen, skyddande tält och värmeisolerade, utsmyckade boningar är sedan gammalt. Men att väva en spatial upplevelse – det är något annat.

Inom japansk arkitektur, traditionell såväl som samtida, finns ett sätt att se på rumslighet som en subjektiv upplevelse, ett fysiskt minne och en fortlöpande process i den mänskliga hjärnan. I Ytans materialitet (2009) skriver Fridh och Laurien om hur rumsliga upplevelser är något pågående abstrakt snarare än en form. Textil skulle i dessa teorier kunna utgöra ett exempel på ett flexibelt material vars transparenta lager eller reflektioner ihop med ljus stimulerar psyket. Textilens taktilitet, flexibilitet och tvådimensionella yta kan upplevas som tredimensionell och spatial tack vare sin föränderliga karaktär.

Jag som skriver denna artikel hyser ett stort intresse för perception, här i betydelsen upplevelse, och i min konstnärliga praktik har tredimensionell vävning kommit att förkroppsliga rumslighetens tankevärld. När min bror för ett tag sedan ställde den filosofiska frågan: “vad är ett mellanrum?”, fanns inget snabbt svar. Mellanrum kan vara ett område eller ett avstånd mellan två högst konkreta objekt, men det kan också existera mellan två abstrakta ting. Multilager har varit mitt tekniska tema så länge jag vävt: ett sätt att skapa allt från tredimensionella ytor till arkitektoniska moduler vävda i ett stycke – små rum om en så vill. Ibland mikroskopiska, ibland så stora att en skulle kunna krypa in. Dessa rumsligheter liknar egna små världar där sinnet lämnas fritt att fantisera.

Något drömskt skapas mellan de vävda väggarna. Rent psykologiskt, i linje med Fridh och Lauriens teorier, bidrar den optiska effekten som uppstår då ljuset studsar och filtreras genom lagren till en spatial upplevelse. Yttexturer och mönster samspelar med form, form med rummet runtomkring, färg, ljus och skugga med den spatiala perceptionen. Men här skapas också metaforer: mellanrum som uttryck för längtan efter space. Efter tystnad, långsamhet, tid.

Det finns också platser för att sörja eller hata, till exempel mellan dörrarna där posten kommer in. Tamburdörren har små gröna och röda glasrutor, den är smal och högtidlig och tamburen är full av kläder, skidor och packlårar men just mellan dörrarna där man nätt och jämnt får rum finns ett ännu mindre utrymme för att stå och hata. Om man hatar i ett stort rum dör man genast. Men om det är smalt går hatet inåt igen och runt kroppen så att det aldrig hinner fram till Gud.

Tove Janssons beskrivning i Bildhuggarens dotter (1968) av rummet mellan de dubbla ytterdörrarna biter sig fast i mig. Den kopplar de vardagliga föremålen till de starkaste känslorna, fysiskt och andligt samsas. I mitt textila rum ryms både praktiska trasmattor, en fårfällimiterande rya i sängen, skira gardiner genom vilka ljuset strilar in och figurativa änglamotiv som får mig att tänka på andra dimensioner.

Textil besitter förmågan att definiera rum. Och detta är anledningen till att jag säger mig väva hela rum. Min ambition är att erbjuda människor en upplevelse av mellanrum; en plats för sinnet att vila. En paus från samhällets informations-overload.

Jag skulle vilja bena ut skillnaden mellan engelskans feeling, emotion och sensation – tre begrepp som vi på svenska litet slarvigt översätter till känsla. Såväl emotion som sensation finns även som svenska ord. Feeling är kanske just en känsla av blandat slag, medan emotion är en sinnesrörelse eller känslostämning. Slutligen har vi sensation: detta aningens försakade begrepp, som beskriver en sinnesförnimmelse eller kroppslig upplevelse.

Här kopplar jag på Josef Albers, Anni Albers man. Denne menade att konst har att göra med diskrepansen mellan fysiskt faktum och psykologisk effekt. Psykologiska effekter kan benämnas perception, ett begrepp jag i mitt masterarbete i tredimensionell handvävning tog fasta på. Men i stunden vill jag stanna till vid det faktum att både målaren och vävaren arbetar med kroppsliga reaktioner och psykologi när de använder optiska effekter för att slå an på sensationerna.

Tid kan se olika ut. Vad jag upptäckte under mitt examensarbete är hur tid förkroppsligas då händelseförlopp skönjs. Genom att synliggöra tillverkningsprocessen och inte sudda ut spåren efter handens arbete, och genom att låta dygnets ljus spela över ytor och material, blir den rumsliga handväven på flera sätt ett manifest för tid. I arbetet med The Metamorphosis of Weaving undersökte jag på detta sätt mellanrum och upplevelsen av just dagssländelika sensationer. Ytor, mötet mellan ytor och mötet mellan yta och form skapar en spatial perception då betraktaren ser på eller rör sig runt ett föremål. Informationen flödar: den må ha utseendet av en blänkande eller skrovlig yta, eller kanske handlar den snarare om kompositionen i rummet – men dechiffrerad ser vi att den innehåller stimulans, välmående och är en form av ordlös kommunikation, ett bollhav att pausa i. (Skönt.)

The Metamorphosis of Weaving handlade om att göra tråd för storskalig, tredimensionell vävning. Projektet hade en ambition om att i en begränsad tidsram koppla ihop spatiala teorier med handvävning, och som ett sätt att bemästra detta var tråden så illa tvungen att komma upp i skala. Följaktligen bestod inslagen av rep och mattrasor. Jag ville att arbetet skulle göra avtryck på betraktaren, få det att kännas i kroppen. Att skapa något större än mig själv blev nödvändigt för att ta reda på hur perceptionen av tredimensionell form, mikro- och makromönster, texturer och färger i relation till varandra påverkade betraktaren. Sex lager handvävdes i ett stycke och jag såg de undre fem lagren först när väven installerades med skylift på Textilmuseet i Borås. Jag var totalt slutkörd och när jag tittade på det jag vävt var det med lika delar tomhet och förundran.

Metamorfos betyder förvandling. Förvandling eller förändring kan bestå i, som jag i denna text försökt ringa in, rumsliga förnimmelser som uppstår i samspelet mellan ljus, textil och rörelse. Men väv står i dag också i ett spännande skede, en vävens väckelse, där väv som teknik återupptäcks av nya utövare och därmed emellanåt tar annan skepnad. Det tredimensionella vävandet är inte enbart relevant för industrin, det är ett formgivarens intresse för vävtekniska utmaningar bestående av trådar som rör sig i multipla lager och ett hantverk som digitaliseras och möjliggör invecklade vävnoter.

Vävning som ett berättande där tråden agerar huvudperson, textil som text, är en fantastisk liknelse. Kanske blir detta aldrig så konkret som för mattrasevävaren: ett tygstycke löses upp och klipps till trasor och inslag för inslag byggs mönstret, likt Kasuri, upp igen. Ju skickligare vävare, desto mer information om vävens tillkomst kan denne utläsa. Tråden, eller linjen, konverserar. Men den skapar också ytor. Kandinsky noterade 1926 att en särskild kapacitet hos linjen är dess förmåga att bilda yta. Och ytor bildar i sin tur, som vi konstaterat, rum. Att, som i arbetet med The Metamorphosis of Weaving, röra sig över ett fält som spänner från trådtillverkning till hela rum – det är vävpower. Det är att kliva in i rollen som Sensation Director.

TEXTILE SPACES

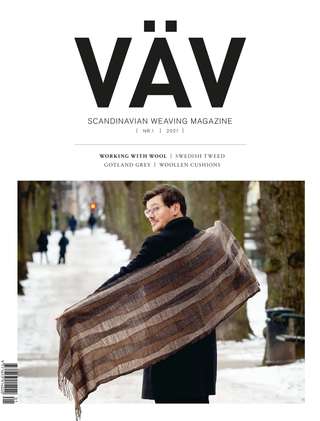

Article for Scandinavian Weaving Magazine 2021.1

TEXTILE TACTILITY

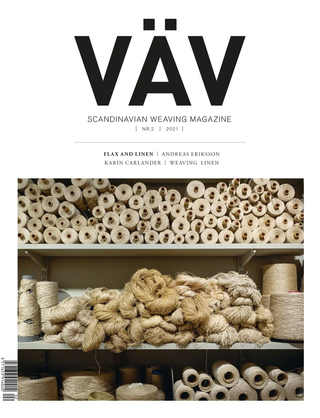

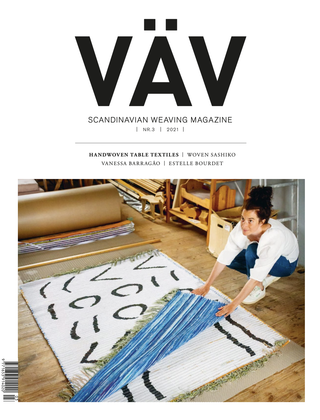

Article for Scandinavian Weaving Magazine, 2021.2

TEXTILE TECHNOLOGY

Article for Scandinavian Weaving Magazine, 2021.3

The Metamorphosis of Weaving

Master thesis, 2020

JavaScript is turned off.

Please enable JavaScript to view this site properly.